Obstructive Fibrinous Tracheal Pseudomembrane: A Very Rare and Life-Threatening Complication of the Endotracheal Intubation-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Pediatrics

Abstract

Obstructive fibrinous tracheal pseudomembrane is a

rare complication associated with endotracheal intubation. We report the

case of a 10-year-old boy hospitalized for a severe abdominal trauma.

The boy remained intubated for 4 days. After extubation he started to

have stridor and acute respiratory distress so a reintubation was

necessary. After 24 hours, an elective extubation was performed and the

boy presented stridor and dyspnoea with no improvement with medical

treatment. A fibrinous mobile membrane was seen during a flexible

bronchoscopy. The pseudomembrane was removed and the patient remained

asymptomatic. The knowledge and an early diagnosis of this pathology is

very important due to be a life-threatening complication.

Introduction

Damage of the airways caused by intubation is usually

associated with mechanical trauma caused by the endotracheal tube

(ETT). Stridor occurs in approximately 1-16% of the patients, but in

4-8% of these children the extubation fails and an urgent reintubation

is needed. The most common causes are laryngeal or tracheal edema. The

symptoms are usually presented within 1-4 hours after extubation and are

usually resolved in under 24 hours. Stridor can persist in spite of the

treatment with nebulized epinephrine and steroidal therapy or with

repeated extubation failures. In such cases, a fiberoptic bronchoscopy

and differential diagnosis of common causes including subglottic

stenosis, vocal cord damage or subglottic/tracheal granulomas are all

required [1].

In recent years an infrequent cause of extubation

failure has been highlighted; obstructive fibrinous tracheal

pseudomembrane (OFTP) with a similar presentation of stridor

post-extubation. The knowledge of this pathology and its early diagnosis

is extremely important as this is a potentially life-threatening

complication [2].

Case Report

We present a case of a previously well 10-year-old

boy who was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit after severe

abdominal trauma. The patient was under hemodynamic instability with an

hemorrhagic shock caused by an hepatic and pancreatic laceration. His

trachea was intubated with an appropriately sized 7-mm oral cuffed ETT,

that passed easily into the trachea. A caudal pancreatectomy was

performed. The child remained intubated and was on ventilatory support

for 5 days. The patient had no fever or suggestive signs of infection in

repeated blood testing. The blood culture and tracheal aspirates were

negative. The chest x-ray was normal. A few hours after the extubation,

the boy started to have severe stridor and acute respiratory distress

and a reintubation was necessary. There were no early complications with

the reintubation and the patient improved immediately. Repeated ETT

suction revealed no secretions. After 24 hours, an elective extubation

was performed. Inspiratory stridor and dyspnea started shortly after

extubation with normal SpO2. The cause of the respiratory distress was

thought to be laryngeal edema and this was treated with inhaled

budesonide and intravenous steroidswith no improvement.

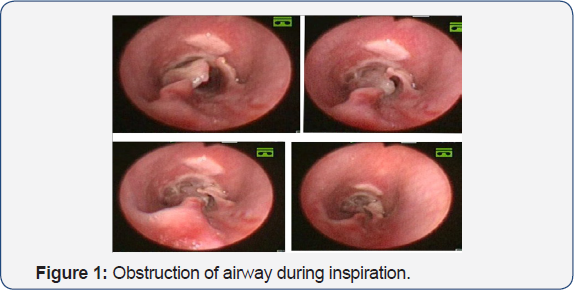

The symptoms became progressively worse and blood gas

results showed increased PCO2, so a flexible bronchoscopy was

performed. In the trachea, a white, fibrinous mobile membrane was seen

two centimeters below the subglottis in an anteroposterior and

transverse position. This caused an intermittent complete obstruction of

the airway during the inspiration (Figure 1). A rigid bronchoscope was introduced and the pseudomembrane was introduced and the pseudomembrane was removed.

The patient remained asymptomatic after extubation

without difficulty breathing or stridor. The control bronchoscopy showed

a normal airway size with a mild erythematous circumferential area.

Secretions or other inflammatory symptoms were not observed. 21 days

after admission the child was discharged home asymptomatic with no

further complications.

Discussion

OFTP is a very rare and life-threatening complication of the endotracheal intubation. The first case was described in 1999 [2].

Birch described the first pediatric case in the year 2005. A 8-year-old

that developed stridor in the first 24 hours after extubation for

dental surgery with general anesthesia [3].

The real incidence is unknown as endoscopy to review airway injury

after intubation is not a routine process. In 2011 a short series was

reported in which a total of 24 adult patients were described and a

review of the literature was made[4].

It is usually not considered a complication after a bronchoscopy in

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) patients or in Neonatal Intensive

Care Unit (NICU) patients. However, a recent retrospective study

performed over a 10 year period describes OFTP in 1.4% of PICU or NICU

patients who had symptoms or clinical signs after extubation [1].

The hypothesis is that the pseudomembrane formation is caused by an

ischemic injury of the tracheal mucosa and submucosa, which causes

ulceration and necrosis. Finally, a fibrinous exudate and an

infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils can be observed, causing a

functional stenosis [5].

The tracheal ischemia due to cuff pressure injury of the ETT has been

suggested as the etiology, nevertheless it has been reported in children

intubated with no tracheal cuff [1,3].

It is also associated with traumatic intubation or inappropriately

large ETT. The OFTP can occur in patients within a short time of

intubation; however the average time of previous intubation is 37 hours.

The clinical presentation consists of stridor and a different grade of

dyspnea that typically occurs before 24 hours postextubation in the

pediatric patients. In adults this can occur 10-15 days later [4].

An important difference between OFTP and laryngeal edema is that OFTP

does not respond to medical treatment. Differential diagnosis includes

staphylococcal tracheobronchitis with tracheal pseudomembranes. In these

cases, cultures could be positive, sepsis could be a clinical

presentation and the lesion might not necessarily be localized to the

site of the cuff or in the subglottis area. Bronchoscopy is used to

diagnose OFTP. The typical endoscopic findings are circumferential

membranes firmly attached to the trachea that move (or not) in the

airway with the respiratory cycle. It can collapse the airway

completely. It can be an annular or flapping septum. The lesion is

located in the subglottis and the first tracheal rings. The rest of the

airway is normal. Standard treatment includes rigid bronchoscopy and

removal of the tracheal membranes. However, a flexible bronchoscopy with

forceps or mechanical removal with a tracheal balloon can also be

useful. There is no sequela. In some cases described in adults the

condition fully resolved after expectoration with spontaneous membrane

removal [5].

Conclusion

In conclusion, in patients with clinical symptoms of

stridor and dyspnea after extubation that does not improve with medical

treatment it is important to think about the formation of a tracheal

pseudomembrane that causes airway obstruction. This obstruction can be

intermittent or positional and can be life-threatening. Pediatric

pneumologists, intensivists and otorhinolaryngologists should know this

pathology for early bronchoscopic diagnosis and treatment.

For more articles in Academic Journal of

Pediatrics & Neonatology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment