Traumatic Pancreatitis in Children-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Pediatrics

Abstract

Traumatic pancreatitis is still a relative

enigma, despite modern clinical practice, technology and modern

diagnostic procedures. This condition is very specific and serious and

is associated with significant morbidity, especially in pediatric

population. Traumatic pancreatitis is also an emerging problem in

pediatric population with its incidence rising in the last 20 years.

Data regarding the optimal management and physician practice patterns

are lacking. We present a literature review and updates on the

management of pediatric pancreatitis due to trauma. Prospective

multicenter studies are necessary to guide care and improve outcomes for

this population.

Keywords: Trauma; Pancreas; Children; Diagnosis; ManagementIntroduction

Traumatic pancreatitis is still a relative enigma,

despite modern clinical practice, technology and modern diagnostic

procedures. This condition is very specific and serious and is

associated with significant morbidity, especially in pediatric

population.

Pancreatic injury is the fourth most common abdominal

organ injury (following injuries of the spleen, liver and kidneys) [1].

Pancreatic injuries are usually very hard to identify by different

diagnostic imaging methods, and these injuries are often overlooked in

patients with multiorgan trauma [2]. Unfortunately, in literature, our

current understanding and approach to the management of traumatic

pancreatitis in children is still based on studies in adult population.

In this article, we will try to summarise current knowledge about

traumatic pancreatitis in children and recommended diagnostic and

therapeutic procedures.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Pancreatic trauma is divided into non-penetrating

(blunt) and penetrating injuries. In children, the most common type of

trauma mechanism is blunt trauma (motor vehicle crashes, falls, violence

and they are typically seen after crashes involving a bicycle

handlebar) [3-5]. There is two typical scenarios: isolated injury caused

by a direct blow to the upper abdomen and multisystem trauma caused by

high-energy mechanisms (usually avulsion of the blood supply by rapid

deceleration, puncture by a fractured rib, or crushing against the

vertebral column) [6,7].

Isolated pancreatic trauma occurs in penetrating

injuries due to anatomic position of pancreas. Pancreatic trauma occurs

in 3% to 12% of blunt injuries, and 1,1% of penetrating injuries in

children [8]. According to the American Association for the Surgery of

Trauma, the guidelines for pancreatic injuries are:

- Grade I: minor contusion without duct injury or superficial laceration;

- Grade II: major contusion or laceration without duct injury or tissue loss;

- Grade III: distal transection or parenchymal injury with duct injury;

- Grade IV: proximal transection or parenchymal injury involving the ampulla;

- Grade V: massive disruption of the pancreatic head [1].

Onset of acute pancreatitis is one of the most serious complications of traumatic injuries.

According to etiology, trauma is the cause of acute pancreatitis in 7,6% to 36,3% [9].

According to literatures, blunt abdominal injuries occur in 10-15% of injured children [10].

Abdominal trauma is the cause of acute pancreatitis in 23% [11].

Suzuki reported that trauma is cause of pancreatitis, even in 36% [9].

Anatomy and Phisiology

Pancreas is an abdominal organ, relatively protected

by ribs. The rib cage provides a bone structural protection. This

protection is less effective during childhood because the ribs in

children are

elastic. In addition, children have relatively larger viscera, less

overlying fat, and weaker abdominal musculature. The pancreas

grows rapidly during first five years of life and after that period

the growth slows down up to the age of 18 years [10].

It is a large complex gland which lies outside the walls of the

digestive tract, parallel to the stomach at the level of the first and

second lumbar vertebrae. The upper abdominal intraperitoneal

organs are situated at the front and paraspinal muscles situated

at the back. The lobules of the pancreas drain into the main

pancreatic duct of Wirsung along the entire gland and joins the

common bile duct, emptying into the duodenum through the

ampulla of Vater [9,12].

Pancreas is not capsuled, so pancreatic enzymes could be

found in the peritoneal cavity. Normally, healthy pancreatic

acinar cells, lysosomes, containing cathepsin B, which is involved

in intracellular and extracellular digestion. Zymogene granules

containing digestive proenzymes (trypsinogen) are released,

and these proenzymes remain inactivated [9]. Even if trypsin is

activated in the pancreas for some reasons, its activity is blocked

by pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. If trypsin leaks into

the blood, the endogenous trypsin inhibitors α1-antitrypsin

and α2 macroglobulin bind to trypsin and suppress its activity.

The sphincter of Oddi prevents reflux of duodenal fluid into the

pancreatic duct [9,13].

Pathophisiology

Pancreatitis is a complex multifactorial disease and more

than one etiological factor may be identified as its cause [14].

Pancreatitis which is the result of trauma may be extended to the

peripancreatic tissues and remote organs [15].

Excessive stimulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion can

cause reflux of pancreatic juices and enterokinase, pancreatic

duct obstruction, and inflammation. These conditions can disrupt

defence mechanisms, activate trypsin beyond the level of trypsin

inactivation, and increase attacking factors leading to acute

pancreatitis [9,15,16]. The activation of zymogene protease in

pancreatic acinar cells plays an important role in the development

of acute pancreatitis [9].

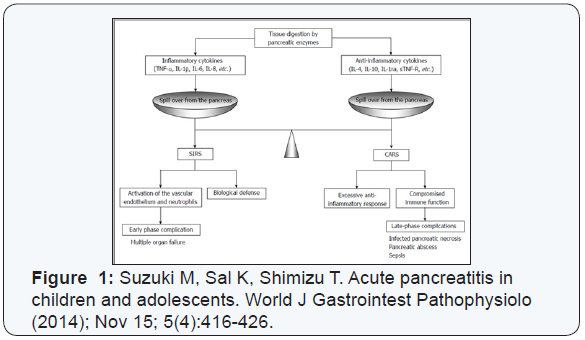

In severe pancreatitis, vasoactive substances such as histamine

and bradykinin are produced in large amounts with trypsin

activation. Because of that, third spacing of fluids and shock due to

hypovolemia may occur. In addition, leakage of activated enzymes

from the pancreas causes secondary cytokine production. These

cytokines trigger the systemic inflammatory response syndrome

(SIRS) [9]. SIRS results in hyper activation of macrophages and

neutrophils, and release tissue injury mediators. In that case we

can expect multi-organ failure and respiratory distress syndrome

[9].

As a biological defence response, anti-inflammatory cytokines

and cytokines antagonists can prevent prolongation of SIRS. This

predominance of antagonists of cytokines is called compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS) [9,17]. CARS

inhibits the production of new cytokines, infection of vital organs

can occur, and as a results of the infection, endotoxins in the blood

stimulate neutrophil aggregation in distal organs, tissue injury

mediators are released, and distal organ failure occurs [9] (Figure

1).

Diagnosis

Pancreas injuries are usually difficult to recognise due to

retroperitoneal position of the organ, and pancreas injuries are

usually not isolated. The diagnosis of acute traumatic pancreatitis

should be kept in mind after every blunt abdominal trauma in

children! Typical trias symptoms in acute pancreatitis in children

are: pain, leukocytosis and elevated levels of serum amylase.

Clinical symptoms

Abdominal pain is an important early symptom in children.

In older children, the frequency of abdominal pain is similar to

the one in adults, whereas in younger children vomiting is an

important clinical symptom [9,16]. Other symptoms are: jaundice,

fever, diarrhoea, back pain etc. A child may have bruises, such as a

handlebar mark on the abdomen, or may not have any marks at all.

Imaging

A plain X-ray of the abdomen in patients with pancreatic

trauma is nonspecific, but it is valuable in prediction of severity.

Conventional radiography can be valuable in detecting penetrating

trauma [2,6,9]. Ultrasonography is a convenient and non-invasive

test. An ultrasound is usually performed to enable the diagnosis

of free abdominal fluid or gross damage to the liver or spleen. The

pancreas is not easy to identified, so pancreatic injuries can be

missed [6,18]. However, it is a very useful method of diagnosis and

evaluation of complications.

CT scans provide the best overall method of diagnosis and

recognition of a pancreatic injury [19]. MRCP (magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography) is a non-invasive procedure for

diagnosis of the integrity of pancreatic duct with high sensitivity

and specificity. MRCP is also very useful in searching for cause of

acute pancreatitis in children [2,6,9].

ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography)

was reported as very useful diagnostic method for pancreatic

duct injury, and it also can be a definitive test to demonstrate the

location of duct disruption and the grade of disruption. Also, ERCP

is an effective and safe non-operative treatment tool [6].

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations are usually non-invasive and nonspecific

as a diagnostic method for traumatic pancreatitis. Raised

level of amylase in serum can be useful in diagnosis, but there is

poor correlation between raised amylase and pancreatic trauma,

because amylase may also be elevated in injuries of the salivary

gland, in duodenal trauma, hepatic trauma, injuries of head and

face [2]. A raised amylase level after blunt trauma of pancreas

is time dependent, and a persistent elevation is an indicator of

pancreatic trauma, but it does not indicate the severity of the

injury [2]. Low disease specificity is a problem [9].

Activity of serum lipase is also not specific of pancreatic injury

[9]. The problem is a low disease specificity (sensitivity is 86,5-

100% and specificity of 84,7%-99,0% for diagnosing pancreatitis).

Its sensitivity is higher in comparison to serum amylase 99). In

severe pancreatitis, serum lipase level is seven times higher than

normal within 24 hours after onset of pancreatitis [20].

Serum amylase has a shorter half-life and rises earlier than

serum lipase. Other pancreatic enzymes have also been described

as markers of inflammation, including carboxyl ester lipase,

isoamylase and phospolipase-A2 [21]. Other laboratory tests

include: glucose, calcium, triglycerides, transaminases, bilirubins,

white blood cells, urea nitrogen and serum albumin [21].

Therapy

Depending on the grade of the pancreatic injury, available

therapies are surgical or conservative. The initial treatment of

pancreatitis is to withhold oral intake of food and fluid, to prevent

stimulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion. The main goal of

therapy is to be supportive! That includes adequate rehydration,

analgesia, pancreatic rest, restoration of normal metabolic

homeostasis [18].

Pain management

There are no data about which analgesic is optimal for

children with acute pancreatitis. Morphine or related opioids

were used in 94% of children with acute pancreatitis [22]. Despite

concerns that morphine may cause sphincter of Oddi spasm and

thus exacerbate pancreatitis, there are limited and opposing data.

Cochran’s analyses do not support this opinion, but the study was

limited to a small number of children [23].

Hebra suggested that acetaminophen, as a peripherally acting

drug, is the choice for mild pain and elevation of body temperature;

tramadol, as a centrally acting analgesic, is used for moderately

severe pain; meperidine, as a synthetic opioid narcotic analgesic,

is used for severe pain [18]. According to Abu-El Haija et al., newer

medications, including intravenous acetaminophen and ketorolac,

reduce narcotic use in paediatric acute pancreatitis [21]. Suzuki et

al. state that pentazocine, metamizol and morphine are commonly

used medicaments [9].

Intravenous fluid management

Because fluid leaks into the surrounding tissue due to

inflammation associated with acute pancreatitis, adequate

infusion to supplement extracellular fluid is needed during initial

treatment. In severe cases, increased vascular permeability

and decreased colloid osmotic pressure causes extravasation

of extracellular fluids into the surrounding tissue and

retroperitoneum and, later, into the peritoneal and pleural cavity

leading to large loses in circulating plasma volume [24].

We still don’t know which fluid and what volume are optimal

in children. The results of a small study conducted a few years ago

support aggressive approach in fluid therapy [25]. However, the

data obtained in another study reported that excessive hydration

(10-15ml/kg/h) resulted in increased organ failure, respiratory

insufficiency and mortality [24-26].

Most commonly, crystalloid solutions are the choice for

resuscitation [21,27]. Recently, a randomised controlled trial

on the use of lactated Ringer’s solution versus normal saline

(although in adults) found that there is a reduction in the

systemic inflammatory response syndrome in lactated Ringer’s

solution[21,28]. All paediatric patients during intravenous fluid

resuscitation have to have good hemodynamic monitoring.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not recommended in all cases of children with

traumatic pancreatitis. In mild cases of pancreatitis the incidence

of infectious complication is low, and prophylactic antibiotics

are not necessary. However, antibiotics should be considered if

severity increases or complications develop. Antibiotics should be

selected so that there is a good tissue distribution to the pancreas

[9].

Hebra et al., suggested using ampicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem

and cilastatin [18]. A recent meta-analysis from 2015, which

included high-quality trials with prescription of prophylactic

antibiotics within 2 days after hospital admission and within 3

days of onset of the pain, demonstrated a significant reduction of

mortality (7,4% vs. 14%) [29].

Nutritional support

There are no published data in paediatric patients concerning

optimal time for starting nutrition and the type of nutrition which

is optimal in children with traumatic pancreatitis. Children with

acute pancreatitis are at risk of acute malnutrition due to two

conditions: the first is the increase in energy intake ant nutrient

requirements related to their catabolic disease and the second is

iatrogenic or spontaneous oral food restriction. The nutritional

risk is inversely proportional to the age as growth speed and

energy/ nutrient requirements are higher in younger children

[16].

According to recent meta-analyses, enteral nutrition

was

superior to total parenteral nutrition with a lower incidence of

infection and multi-organ failure, resulting in lower mortality rates

and a shorter hospital stay [21,30]. Enteral nutrition prevents

the systemic inflammatory response, luminal stasis, bacterial

overgrowth and bacterial translocation [16]. Enteral nutrition

is superior in children with traumatic pancreatitis because it

prevents acute malnutrition, provides better intake of nutrients

for healing the tissue, modulates systemic inflammatory response

and thus prevents multiple organ failure [16]. Li and co-authors

suggested that early enteral nutrition (within first 48 hours) is

very important [31].

Early enteral feeding should be via nasojejunal tube to avoid

secretion of cholecystokinin, secretin and pancreozymin, and also

pancreatic exocrine function will be on minimum. There is no

difference in the outcomes of polymeric and elemental formulas

and there is no evidence that immune enhancing nutrients or

probiotics are helpful in the management of pancreatitis. Optimal

nutritional therapy in paediatrics should be studied further so

that it can be uniformly applied [21].

Elementary diet formula or formula with oligopeptides seems

to be the best option for maximal suppression of pancreatic

secretion. For these reasons, we can concluded that the most

important are nasojejunal feeding tube, elemental formula and

24-hours continuous enteral infusion [16].

Surgical management

Grade III and higher grade pancreatic trauma need operative

management (resection or possible reconstruction and/or

drainage). However, a recent study shows some controversy and

considers a non-operative management of high-grade pancreatic

trauma [32].

Conclusion

Traumatic pancreatitis is an increasingly recognised clinical

entity which may be the result of improved recognition. Children

are not small adults, and pancreatitis in this population is different

from the one in adults in their etiology, clinical manifestation,

severity and outcome. Well designed prospective studies are

needed in all areas of diagnostics and management of paediatric

traumatic pancreatitis.

For more articles in Academic Journal of

Pediatrics & Neonatology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment