Motor Development of Egyptian Children on the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales-2-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Pediatrics

Abstract

Background: Peabody developmental

motor scale (PDMA-2) is considered one of the most commonly used tests

to assess motor development in preschool children. It provide useful and

comprehensive information for early assessment. It remains unclear if

the standard measured established and currently used are applicable to

Egyptian children.

Objectives: To establish normative data for fine motor developmental skills that can be applicable to Egyptian children.

Methods: 195 Egyptian children

attending nursery schools in Greater Cairo, throughout Egypt were

randomly identified, based on their chronological age (from 36 to 42

months). Each child needed to achieve a screening score of at least 80%

using the Portage Scale to participate in this study. If eligible, and

consent was obtained, each child was subsequently evaluated monthly

using the PDMS-2 for six months, longitudinally.

Results: There are significant

differences for measured subtest items of fine motor development for

Egyptian children when compared with the currently available PDMA-2

normative data, using Z-scores.

Conclusion: Confirmation and

acknowledgement of the differences which may exist among children from

Egypt vs. those used to establish “normative standards” for diagnostic

tools, such as the PDMA-2, illustrates the importance of establishing a

range of different “normative values” as needed, so developmental tests,

such as these, can be applicable to a wider range of geographic areas,

globally. Development of standard measures of motor development for

Egyptian children is needed, so as to serve as a national reference for

all health care staff working in pediatric physical therapy.

Keywords: Egyptian children; fine motor development; portage scale; Peabody Developmental motor scaleIntroduction

The field of study concerned with the description and

explanation of changes in motor performance and motor control, across

the life span, is typically called motor development. While the study of

motor development has historically focused on the period from

conception through to adolescence, and the changes and stages through

which the developing human progresses in attaining adult levels of motor

performance, researchers in this field are now also increasingly

interested in the deterioration of motor skills apparent in the elderly

population. Such a broadened focus is important given aging populations

worldwide and given that many changes in the performance and control of

motor skills are age related and occur throughout the entire life span

[1].

Children are the biggest promise for the nation’s

future. The family, community, and government are responsible for their

survival, development, and protection. The Egyptian government took

successful steps in saving children’ life through promoting diarrheal

disease control, vaccination and Integrated Management of Childhood

Illnesses (IMCI). It now focuses on child development programs aiming

creation a more physically and mentally productive generation. The long

term progress of any nation depends on how much it cares about its

children [2].

Fine motor skills are the collective performances

that involve the hands and fingers. That is, fine motor skills are those

performances that require the small muscles of the hand to work

together to perform precise and refined movements. Fine motor

skills typically develop in a reasonably consistent and predictable

pattern in the early years of childhood (from birth through to mid

primary school). They include reaching, grasping, manipulating

objects & using different tools like crayons & scissors. But

because

tasks such as printing, coloring & cutting are not emphasized

until a child is of preschool age, fine motor skill development is

frequently overlooked when the child is an infant or toddler [3].

The Peabody Developmental Motor Scales-2 (PDMS-2) is the

most commonly used pediatric motor outcome measurement

tool. The PDMS-2 was designed to assess motor development

in children from birth to 72 months of age to measure fine and

gross motor skills. The possible uses of the PDMS-2 include;

Determination of motor competency relative to a normative peer

sample, assessment of qualitative and quantitative capacities

of individual gross motor and fine motor skills, evaluation of

progress over time and determination of efficacy of interventions

in research [4].

The motor development of children is a critical developmental

and an important area for scientific research. We believe that

despite its importance to children, the field of motor development

and physical therapy has remained disappointingly neglected and

we believe that we need to confirm that the current standards

being used are appropriate and applicable to Egyptian children,

and if not that a standardized scale which measures the normal

development of Egyptian children be created and used.

The PDMS-2 is one of the most popular used scales all over

the world, however it only examined children from western

populations, and as such it is not clear if the populations used

to create the normative values are broadly applicable to those

of all children, and in particular those from Egypt. The need to

establish a fine motor scale that is representative to the fine motor

development in Egyptian children is needed. There has been no

study conducted to check the applicability of the PDMS-2 in Egypt.

Thus, the regional relevance of the PDMS-2 must be examined,

specifically when scores are used to determine whether a child is

“normal” or delayed. Therefore; it was very important to establish

norms for the Egyptian children in fine motor developmental skills

to find a way of assessment that might be more clinically relevant

for Egyptian children.

Methods

Sample

An estimated cluster sample of three governorates from the

total governorates represented in the Greater Cairo Area, Egypt

was studied; reaching a total of 195 participants. Children of either

gender with ages from 36 to 42 months were included. Children

were excluded if they failed the screening test (scoring a value of

< 80% on the Portage Scale), or had active medical conditions or

were uncooperative on 3 trials.

Instruments

The Portage checklist has been introduced successfully into

countries across the world and translated into different languages,

Arabic version. It focuses on the role of daily contact with the child

recognizing the critical importance of the interactions taking

place between parent/care and child in promoting the early

development of the young child. The Portage kit is an Activity Card

File that consists of 580 developmentally sequenced questions

from birth to age nine, it contain five domains: Socialization, Self-

Help, Language, Cognition, and Motor.

PDMS-2 norm-referenced and standardized motor skill test

that consists of 6 subscales of which the scores from 4 subscales

that combined to give a gross motor quotient (GMQ) and 2

subscales combined to give a fine motor quotient (FMQ). For each

item, the manual describes the child’s beginning position, the

materials needed, and directions for administering the item and

the criterion for scoring. The criterion for scoring each response

is written in a behavioral objective format which specifies the

number of trials permitted or the time allotted. Each response is

scored on a 3-point scale (0 _ unsuccessful, 1 _ clear resemblance

to item criterion but criterion not fully met, 2 _ successful

performances, criterion met). The administration of both Gross

Motor Scale and Fine Motor Scale takes approximately 45 to 60

minutes [5].

Procedure

Subjects were recruited for the study from nursery schools

and play schools in Egypt. Screening was done by administering

the Portage Checklist as per the guidelines given in the scale. The

child was included in the study if they achieved a score of at least

80% according to the portage motor checklist.

The PDMS-2 was then administered according to guidelines

provided in the manual, using the floor and ceiling rules to

minimize the administration time. The data were recorded in

the examiner record booklets. The obtained raw scores for visual

motor integration subtest of the scale were converted to age

equivalent, percentile, and standard scores. All the values were

recorded on the summary score sheet. The standard scores and

the quotients were converted to z-scores for analysis were used

for comparison with the normative mean values in the PDMS-2

manual.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS ver.14.0 and Arcos software

packages. The mean and standard deviations were calculated for

the raw scores, standard scores, for age group (36–42 months).

The z-scores for the standard scores for fine motor scale were

calculated and compared with the normative z-scores provided in

the manual.

Results

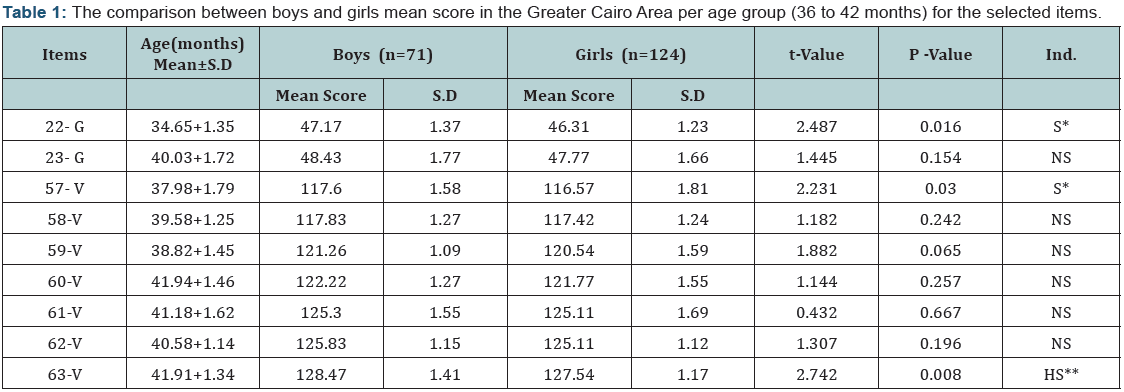

The three groups of Egyptian children from Greater Cairo Area

(Cairo, Giza, and Kaliobia) were homogenous in mean age. Mean ages of Greater Cairo Area were calculated in one group. The mean

age (in months), the mean, and standard deviations for the raw

scores of selected items for both boys and girls were according to

the child’ chronological age (36 to 42 months) presented in Table1.

The measurable items for this age were two items of grasping

subtest of PDMS; 22- G: Grasping marker, 23- G: Unbuttoning

button and seven items of visual motor integration subtest; 57- V:

Cutting paper with blunt scissor, 58-V: Lacing string into 3 holes,

59-V: Copying cross, 60-V: cutting on the line drawn, 61-V: Copying

cross in the middle, 62-V: Dropping 10 food pellets, and 63-V:

Tracing line drawn, With taken into consideration the basal and

the ceiling level of scoring according to the Illustrated Guide for

Administering and Scoring of the PDMS-2 Items.

The sample of this age includes 195 children, 71 of them are

boys and 124 are girls and we report here the statistical analysis

of all data collected. Descriptive analysis for the mean values of

Egyptian children development during this study for this age was

shown to have a significant statistical difference between boy and

girl groups in 22-G, 57-V, and it highly significant in 63-V items.

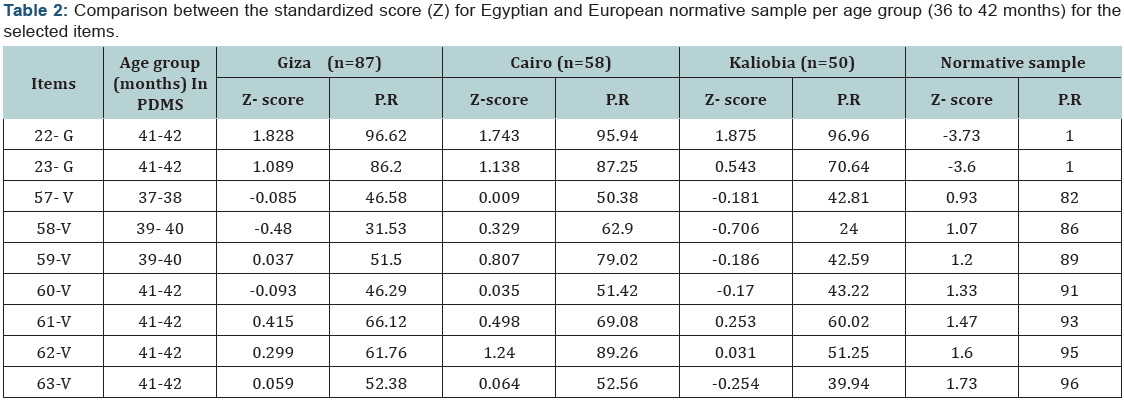

The statistical analysis of the Z-score and percentile rank of

the standard scores for this age group indicated that there was

a significant difference between the three groups of Egyptian

children from greater Cairo area (Cairo, Giza, and Kaliobia) and

the normative sample in favor of Egyptian children in grasping

items and in favor of European sample in visual motor integration

items; were presented in Table 2 and shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

Development is influenced by heredity and environment. One

of the environmental factors that affect development is culture

which may affect performance of a child on a developmental test

that does not reflect typical cultural experiences for a specific

population. Because differences in motor development have been

found among various ethnic groups, the cultural relevance of

standardized developmental tests must be examined [6].

Uses of scales that are developed for western populations

are not always applicable to all the diverse cultural groups and

regions of the world, so that the cultural and regional relevance of

a scale must be checked before using. Such a project is especially

important because these tests are used to determine whether a

child is developing typically or is in some way delayed, requiring

special services [7].

Motor assessments designed for children of the dominant or

mainstream culture are not always appropriate for those from

diverse ethnic backgrounds. This study was undertaken to compare

the scores of children from one ethnic group with the scores of the

children on whom the test was normed. It was observed that there

were significant differences in the scores of the children from our

sample, compared with the normative data given in the manual of

PDMS-2. It indicates that cultural differences could significantly

affect the scores of the children on the scale [8].

The ages of the study population ranged from 36 to 42 months.

It contains two items of grasping subtest of PDMS; Grasping marker

which develop earlier in Egyptian children around 34 months than

in the normative western-derived sample around 41 months and

Unbuttoning button which develops in Egyptian children around

40 months and in the normative sample around 41 months, along

with seven items of visual motor integration subtest; Cutting

paper with blunt scissor which develops in Egyptian children

around 37 months as in the normative sample, Lacing string into 3

holes which develops in Egyptian children around 39 months as in

the normative sample, Copying cross which develops in Egyptian

children around 39 months as in the normative sample, cutting

on the line drawn, Copying cross in the middle, Dropping 10

food pellets, and Tracing line drawn which develops in Egyptian

children around 41 months as in the normative sample.

The grasping and the visual motor integration skills that were

to have a highly significant difference in the mean standardized

(Z) score of the third group, in favor of Egyptian children for

grasping items and in favor of European children for visual motor

integration items. Growth potential in preschool children is similar

across developing countries, and stunting in early childhood is

caused by poor nutrition and infection rather than by genetic or

geographical differences. Patterns of growth retardation are also

similar across countries. Faltering begins in utero or soon after

birth, is pronounced in the first 12–18 months, and could continue

to around 40 months, after which it levels off [9].

The higher performance in grasping subtest is seen from the

age of 36 months and is maintained until the age of 54 months,

reaffirms the findings of another study that suggested that the

increase in maximal isometric grip strength during childhood and

in preadolescence stages has two components; The first is muscle

growth, which takes a gender-specific course during puberty,

indicating that it is influenced by hormonal changes. The second

increase in grip strength per muscle cross sectional area (CSA)

[10].

While the lower performance of visual motor integration

subtest, seen from the age of 36 months, could be better understood

applying the findings from another study which reported that the

hand represents an excellent model in which to study one of the

most intriguing issues in motor control: simultaneous control of

a large number of mechanical degrees of freedom. The complex

apparatus of the human hand is used both to grasp objects of all

shapes and sizes through the linked action of multiple digits and

to perform the skilled, individuated finger movements needed

for a large variety of creative and practical endeavors, such as

handwriting, painting, sculpting, and playing a musical instrument

[11].

Conclusion

In general, the findings reported here confirm several

significant differences between the scores of children 36 to 42

months from the Greater Cairo Area, Egypt, and those of the

western-generated normative sample used as a standard or

normative comparator in the currently available version of the

PDMS-2.

It is not always practical to develop assessment tools which are

culturally sensitive across the totality of regions and environments

where they may be needed and used, but it is necessary to evaluate

the cultural and geographical differences that may be evident

for standardized tests for a particular region and ethnic group,

especially when these instruments are being used to assess areas

of motor development of Egyptian children and serve as a means

of access to important and needed therapeutic resources. We may

be unknowingly limiting access to children who would benefit

from therapeutic help, and providing to others who are less

likely to need or benefit from it. Applicable standards for motor

development that are relevant to Egyptian children are needed.

Acknowledgment

Thank you to Prof. Dr. Faten Abdelazeim and Prof. Dr. Amany

Mousa for their review of the manuscript. The authors thank

the children and the families who participated in this study; the

staff of the various nursery schools and baby class members for

assistance in recruitment and use of their facilities for the support

of this study.

For more articles in Academic Journal of

Pediatrics & Neonatology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment