Cervical, Mediastinal, Intraspinal and Paraaortic Emphysema Secondary to Asthma Exacerbation Case Report-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Pediatrics

Abstract

Cervical and mediastinal emphysema associated with

acute asthma exacerbation is very rare. In most cases, air leakage from

ruptured alveolar escapes and dissects the hilum along

peribronchovascular sheaths and spreads to mediastinum. Once in the

mediastinum, air extends around the large vessel and esophagus to

thoracic wall. This report presents the case of 3 years old patient with

background of asthma who presented to the emergency room with palpable

cervical emphysema, wheezy chest and CT evidence of cervical and

mediastinal emphysema. There are only a limited number of case reports

associated with cervical and mediastinal emphysema in the absence of

pneumothorax in patient with asthma.. To our knowledge, this maybe the

first report in pediatric where cervical, mediastinal, intraaspinal and

paraaortic emphysema is induced by asthma exacerbation in the

literatures.

Keywords:Asthma; Emphysema; PediatricIntroduction

Cervical and mediastinal emphysema associated with

acute asthma exacerbation is rare. This report presents 3-years old boy

with recurrent asthma who presented with clinical significant cervical

emphysema. Only limited number of cases have been reported with cervical

and mediastinal emphysema in the absence of pneumothorax in patients

with asthma.

Case Presentation

A 3 years old boy presented to our emergency

department with cough, fever, shortness of breath, vomiting, muffled

voice and throat pain for 2 days. He had history of recurrent chest

wheezing attacks that were controlled by salbutamol nebulization. There

was no history of contact with sick patients or animal pets. The child

was fully vaccinated. He had manifest distress and his oxygen saturation

on room air was 95%. His temperature was 38.5 °C, respiratory rate was

58per/min and heart rate=125/min. The Neck was swollen with crackling

sensation due to subcutaneous emphysema. Sub costal and inter costal

retraction was evident. On auscultation there was bilateral wheeze heard

all over the chest. He was started on 5 L oxygen, salbutamol Nebulizer.

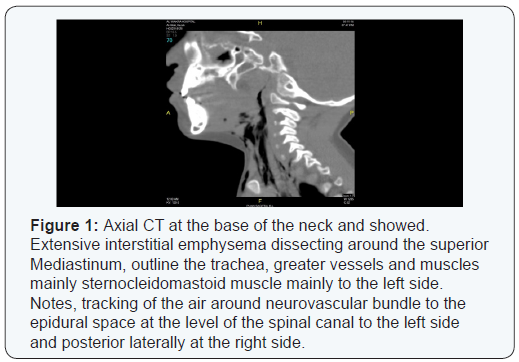

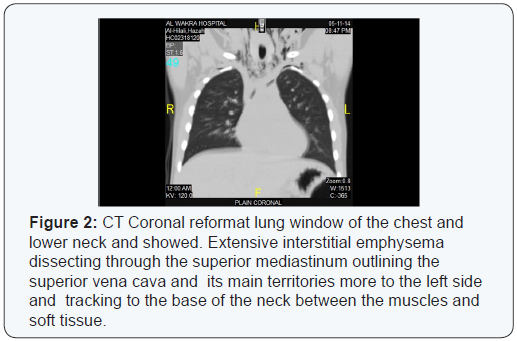

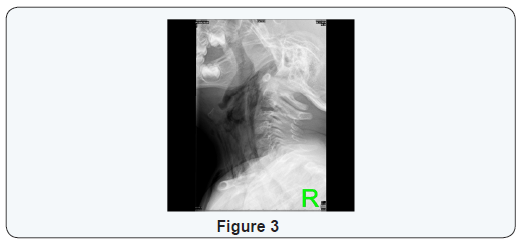

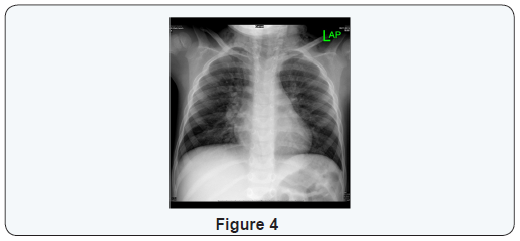

Lateral neck radiography showed increased thickness

in the nasopharyngeal region and narrowing in the nasopharyngeal air

column. CT scan of the neck revealed extensive air in the

retropharyngeal space extending to the subcutaneous tissue of the neck,

mediastinum and interaspinal canal. CT chest shows some air noted

surrounding the aorta at the D 12 level. The lung parenchyma showed

exaggerated broncho-vascular markings and mild septal thickening. The

patient was shifted to pediatric ICU where he was started on high flow

oxygen, intravenous antibiotics and continued on salbutamol nebulizer.

Within 3 days of hospital admission he showed dramatic clinical and

radiological improvement.

Discussion

Cervical and mid mediastinal emphysema may occur

secondary to bronchial asthma, retropharyngeal abscess or lateral space

abscess. Pneumo-mediastinum (PM) usually results from the over

distension of the alveoli, with rupture, allowing air to enter

interstitial tissues and extend into the mediastinum, neck, or

intrathoracic areas. Wong et al. [1] analyzed 87 children with

spontaneous pneumothorax. Forty-three patients (49.4%) had a primary

idiopathic spontaneous pneumothorax (SPM). The most common cause of

secondary SPM was bronchial asthma with an acute exacerbation. None of

the patients <6 years (n=16) had primary PM while 60% of patients

>6 years had primary PM (0% vs 60%) Therefore, a high index of

suspicion for underlying causes

of SPM should always be kept in mind for young children younger

than 6 years [1].

Bronchial asthma predisposes to the development of

SPM [2] because asthma augments airway epithelial injury

and increases alveolar rupture due to lung hyperinflation

[1]. Pneumomediastinum is defined as the presence of free

air in the mediastinum. It can be divided into spontaneous

pneumomediastinum (SPM) (without any obvious primary

source) and secondary or traumatic pneumomediastinum due to

a mediastinal organ injury caused by trauma, surgery or medical

procedures. According to Macklin’s experimental animal model,

alveolar rupture leads to air infiltration along the bronchovascular

sheath with free air finally reaching the mediastinum. Furthermore,

if the air travels along tissue planes it can reach the neck, face,

abdomen or even the limbs, leading to subcutaneous emphysema

[3].

SPM was originally described by Louis Hamman in 1939 (34),

while later it was identified as Hamman’s syndrome. Sudden onset

of symptoms of SPM include retrosternal pain (80%), rhinophonia

and/or hoarseness (65%), dyspnea (46%), cough (26-45%),

subcutaneous emphysema (32%), sore throat (18%), and neck

pain (4-38%) (43). According to several reports, the most common

presenting complaints are chest pain, shortness of breath and

subcutaneous emphysema. The diagnosis of pneumomediastinum

is based upon radiographic examination. CT chest scan is a better

means of diagnosis compared to plain chest X-ray film [4].

Management of Pneumomediastinum depends upon

whether or not it is complicated. Uncomplicated SPM is managed

conservatively with analgesia, rest, and avoidance of maneuvers

that increase pulmonary pressure (Valsalva or forced expiration,

including spirometry). Therapy with high concentration oxygen

has been used in an effort to enhance nitrogen washout, but is

probably not necessary except in patients with severe symptoms.

If such patients have underlying chronic lung or airway disease

that predisposes to atelectasis, 100 percent oxygen therapy should

be administered with caution, because it may lead to absorptive

atelectasis [5].

Massive pneumomediastinum may be complicated by tension

pneumomediastinum, which may interfere with breathing or

venous return. In this case, limited mediastinotomy may be

performed to drain the pneumomediastinum [5]. The outcome

of SPM is usually good and this benign condition usually resolves

without consequences within 2 to 15 days, often after a transient

worsening of symptoms. Recurrent SPM occurs in less than 5

percent of cases, and such recurrences are typically also benign

[6].

Learning Points

Although cervical and pneumomediastinum is a rare

complication of asthma in pediatric age group, specially

those who are less than 6 years, it should be considered

always in the differential diagnosis. The clinical presentation of pneumomediastinum secondary to asthma exacerbation

varies widely, so imaging study, including CT scan and X-ray are

recommended to narrow the differential diagnosis. Supportive

measurement is a treatment modality in most of the cases, but

surgical intervention is needed in some of the cases (Figure 1 to

4).

For more articles in Academic Journal of

Pediatrics & Neonatology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment