Analysis of Tools for Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Indian Context-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Pediatrics

Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a

neurodevelopmental condition with varied manifestations and poses a

diagnostic challenge. The prevalence of ASD has increased in a highly

populated and demographically ‘young’ country like India. However,

prevalence rates are varied due to differences in measurement methods.

Moreover, caregivers tend to delay reporting for developmental concerns

as compared to physical health problems. The current analysis focuses on

two common diagnostic tools used in India for ASD i.e. the fifth

edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and

the Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism; and compares these tools

with the revised Autism Diagnostic Interview. The analysis describes

strengths and limitations of each of these tools and provides

recommendations for their use in outpatient clinical practice.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder; Diagnosis; Analysis; India, DSM-5; ADI-R; ISAAAbbreviations: ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ISAA: Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism; ADI: Autism Diagnostic Interview

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a

neurodevelopmental condition with highly varied manifestations and poses

a diagnostic challenge. First, as per the fifth edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the

current definition of ASD broadly includes features of previously known

conditions such as ‘classic autism’ (or Kanner’s autism), childhood

disintegrative disorder, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise

specified, as well as Asperger syndrome [1]. Although individuals with

ASD have persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, as

well as restricted and/or repetitive behaviors, the clinical features

are part of a ‘spectrum’ i.e. each individual has different degrees of

impairment, marked by combination of symptoms of varying severity [2].

Second, the etiological approach to diagnosing ASD (unlike several other

physical or mental health conditions) is impractical. Genetic risk

factors have been implicated to cause ASD [3], as also intake of

valproic acid and thalidomide in pregnancy [4-5], in addition to routine

perinatal complications [6], increased parental age [7] and birth

defects associated with dysfunction of the central nervous system [8].

Definitive evidence on implicating these risk factors as causative

agents has not been established. Third, in the Indian context,

caregivers tend to delay reporting of developmental concerns, as

compared to physical health problems [9]. Thus, initial evaluation or

diagnostic impression of ASD needs to be comprehensive and

individualized to the child’s needs – and not merely sensitive in

detecting the condition. This is decisive in framing the goals and

strategies of an intervention program.

Finally, from an epidemiological perspective, the

prevalence of ASD has increased in a highly populated and

demographically ‘young’ country like India. However, prevalence rates

are varied due to differences in measurement tools [10-12]. Studies have

reported prevalence of 1 in 65 children (2-9 years of age, 4000

households), 1 in 500 children (1-9 years of age, 5000 households) and 1

in 1000 children (1-10 years of age, 11,000 children) in different

regions of India. These differences have failed to define the burden of

ASD in the Indian context. Thus, we need a discussion on strengths and

challenges of diagnostic tools for high-prevalence developmental

disorders like ASD, to have a standardized evaluation approach.

The current analysis focuses on two common diagnostic

tools used in India for ASD i.e. the DSM-5 and the Indian Scale for

Assessment of Autism (ISAA); and compares these methods with the revised

Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R).

A diagnostic tool needs to be culturally relevant, with optimum

sensitivity and specificity. The assessment should exert minimum

demand on professionals, in terms of their required training to use

the tool. It should be feasible to administer in a clinic setting, based

on time and costs. Finally, it should be comprehensive i.e. covering

maximum aspects of the developmental-behavioral profile of

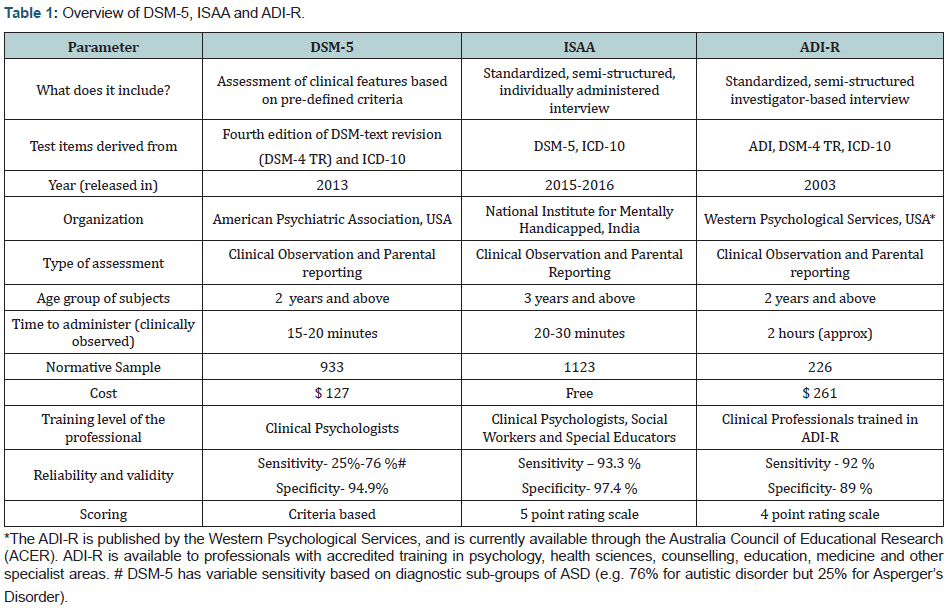

ASD. (Table 1) provides an overview of DSM-5 [1,2,13,14], ISAA

[2,15,16] and ADI-R [17-19].

Analysis of strengths and weaknesses of diagnostic tools:

DSM-5: The strengths of DSM-5 include: (1) DSM-5

provides ‘specifiers’ in addition to the diagnostic impression and

level of severity. The specifiers include accompanying language

impairment; intellectual impairment; associated medical or

genetic conditions or environmental factors; associated neuro developmental, mental or behavioral disorders and catatonia.

Thus, DSM-5 creates scope to identify associated conditions along

with the primary diagnosis.(2) DSM-5 provides severity level for

each criterion (e.g. severity of deficits in social interaction and

communication). (3) DSM-5 can be most rapidly administered, out

of the three diagnostic tools.

Following are the limitations of DSM-5: 1) All previously

defined disorders related to Autism have been grouped under

‘ASD’, which not only reduces the sensitivity (Table 1) particularly

in younger children, but also limits the clinician to fully understand

the (former) clinical sub-types (e.g. pervasive developmental

disorder-not otherwise specified, Asperger’s Disorder, Rett

syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, etc.). This limits the

individualization of an intervention plan to the child’s needs. 2)

DSM-5 does not specify the age-range for emergence of symptoms.

It states that ‘symptoms may not be fully manifest until social

demands exceed capacity’ [20].

ISAA: The strengths of ISAA include:

1) ISAA scores

symptoms through a five-point rating scale, which categorizes the

symptom-frequency (i.e. rarely, sometimes, frequently, mostly and

always). Percentages have been pre-assigned to these categories

based on the validation processes implemented to prepare the

scale [16]. Thus, the categorization improves the specificity of

caregiver’s reporting. 2) An important advantage of ISAA (and

the rationale for its design) is its standardization and cultural

relevance to the Indian population. 3) ISAA can be administered by

professionals besides psychologists, which potentially widens its

applicability in a high-prevalence region like India. 4) Along with

observation and parental interview, ISAA also includes ‘testing’

i.e. the scale has recommended certain activities requiring clinicbased

materials, which can be performed to elicit a response from

the child suspected to have ASD [16]. Several of these materials

are home-based. 5) ISAA provides disability certification based on

scoring. It has been anecdotally observed that such a certification

process, in-built within assessment techniques, has encouraged parents

to report for early intervention in other developed

countries. However, evidence for the same is lacking in the Indian

context. 6) ISAA has the highest specificity out of the three scales.

7) ISAA is free of cost and available in regional Indian languages.

The limitations are as follows: 1) Articulation of some

items, in the ‘Observation and Interview’ section of ISAA is not

adequately clear. This may necessitate the administrator to refer

the manual during evaluation. Examples of few such items include:

“(individual) has unusual vision”, “has unusual memory of some

kind”, “engages in self-stimulating emotions”, “shows exaggerated

emotions” and “shows inappropriate emotional responses”. 2)

ISAA provides a summative diagnosis i.e. an overall score that

categorizes the condition as ‘no’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’

Autism. Thus, no specific severity levels have been provided for

individual sub-domains (i.e. social relationship and reciprocity,

emotional responsiveness, speech language and communication,

behavior patterns, sensory aspects and cognitive component).

3) ISAA can identify Autism only in 3-9 year old children and

certify disability of at least 40%. Further research is warranted to

evaluate its diagnostic value in 2-3 year old children [21].

ADI-R: The strengths of ADI-R include: 1) ADI-R has the

widest age-range out of the three scales. Two diagnostic algorithms

are available for children 2 to less than 4 years of age, and 4 years

and older. Moreover, new algorithms have been made for children

12-47 months of age and those with non-verbal mental age of 10

months, to increase its application [22]. 2) ADI-R provides a score-based

severity level for each domain (unlike DSM-5 that provides

a clinical judgment-based severity level). 3) ADI-R includes the

most number of testing items - 93 items distributed across five

sections i.e. introduction, communication, social development

and play, repetitive and restricted behaviors and general behavior

problems. Thus, due to its detailed nature (viz. items and severity

levels), ADI-R provides the greatest breadth of information

to locate the affected developmental domains in a child, for

designing the most suitable intervention program. 4) ADI-R is

a parent-friendly interview, since the questions are ordered

in such a way that caregivers can inform positive aspects of the

child’s behavior, which reduces the discomfort of giving repeated

answers on negative behaviors. 5) Most items are rated separately

for ‘current’ behavior of the child; as well as the period in child’s

early life, during which the behavior in question was most atypical.

Hence, the degree of detail is not only in the description of current

symptoms, but also their emergence in early life, thus increasing

credibility of the diagnostic impression. 6) ADI-R includes ‘notapplicable’

and ‘not-known’ codes for items (in contrast to >DSM-5

and ISAA) which reduce the bias in scoring items that could be

developmentally irrelevant.

In terms of limitations, ADI-R is the most expensive and

time-consuming of the three tools, apart from the lack of cultural

validation in the Indian context, and the fact that it needs

specialized training, which may take at least two months to

complete [23]. Moreover, in the Indian context, caregivers tend

to focus more on physical health of the child, rather than mental health. Greater emphasis is placed on aspects like academic

ability; while behaviors related to play and social interaction are

often overlooked. Hence, responses by caregivers to the detailed number of items, may not always be appropriate[24].

Conclusion

The analysis compares three common tools for diagnosing

ASD, in a context where screening alone may have little value,

due to delayed identification of ASD and delayed reporting by

caregivers. The authors propose that studies should be conducted

to establish the specific indications where a DSM-5 or an ISAA

will be more appropriate for diagnosis. Studies should also be

conducted to validate ISAA in children younger than two years. In

addition, there is a strong need to revise the articulation of some

items in ISAA that may not be well understood. Moreover, since

ISAA also involves testing, additional training maybe required

for evaluation of certain domains, such as sensory aspects and

cognitive component. In these cases, it will be more appropriate

to modify some components of ISAA, so that professionals of

different skill-sets can use the scale, for example – pediatricians,

physicians, psychologists, special educators and medical social

workers. In contrast, ADI-R mandates formal training and DSM-5

mandates administration only by psychologists.

ADI-R may not be suitable for routine use, given the timeconstraints

in developmental pediatric practice and the cultural

incompatibility with the Indian context. With regard to the latter,

however, it may be an assessment of choice for urban middle-income

and upper-income families. Moreover, there are frequent

situations where a child may have features of ASD but diagnostic

criteria are not met in DSM-5. Such situations could arise in the

use of ISAA as well. Hence, practitioners should take advantage

of the detailed number of items and scoring strata in ADI-R, for

evaluating such children. To that end, the therapy centre needs

to have a trained professional who can administer ADI-R and has

pre-tested the method with Indian parents in order to locate any

items which need modification, based on cultural factors.

For more articles in Academic Journal of

Pediatrics & Neonatology please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/ajpn/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment